By the time the old suitcase was spotted on the side of a lonely country road in South Australia, the little girl inside it had already been dead for years.

The driver who saw it that July day in 2015, near the tiny town of Wynarka, probably didn’t think much of it at first. Australia’s highways are long. Things fall from cars. People dump rubbish. An old case by the roadside doesn’t usually mean anything.

But this one did.

When the passer‑by stopped, opened the battered suitcase and looked inside, they did not find clothes or tools or paperwork.

They found bones.

Tiny bones.

The remains of a child.

—

### A suitcase by the highway

The suitcase had been seen before.

Locals later told police they had noticed a well‑dressed man, believed to be in his 60s, carrying it along the Karoonda Highway near Wynarka some weeks earlier. It was an odd sight: a man in neat clothing, walking in the middle of nowhere with luggage, then leaving without it.

No one called it in at the time.

No one expected that the case would eventually reveal the remains of a little girl, aged somewhere between two and four, packed in among children’s clothes and a handmade quilt.

When the driver who stopped inspected the suitcase and saw what was inside, they found something that did not belong to a doll, or an animal, or an adult: a small jawbone.

They called police.

In the middle of South Australia’s vast, open country, a crime scene was born.

### The child in the suitcase

Detectives converged on the lonely stretch of road.

The suitcase, the bones, the items inside — they were all carefully recovered and taken away for examination. Forensic experts began the slow, careful work of reconstructing a life from fragments.

The child had been dead for years — possibly as long as seven.

Her remains were badly decomposed, but they still held clues: her size, the condition of her bones, the remnants of hair, fabric, and fibers around her. Inside the suitcase were several pieces of children’s clothing and a small, badly degraded handmade quilt.

One of her dresses stood out: pink, simple, the kind of dress thousands of little girls wear on ordinary days. It was heartbreakingly normal.

Yet the setting was anything but.

This wasn’t a child who had died surrounded by family and been buried with care.

She had been packed into a suitcase and dumped by a highway.

Who was she?

How did she end up here?

And where was her mother?

### Another body, another state, another forest

Five years earlier and more than 1,000 kilometers away, trailbike riders had been exploring the Belanglo State Forest in New South Wales — a place already steeped in dark history.

Belanglo lies between Sydney and Canberra, a dense pine plantation surrounded by scrub and dirt tracks. To most Australians, the name is instantly familiar. It was here that serial killer Ivan Milat murdered seven young backpackers in the early 1990s — Britons, Germans, and Australians whose remains were found concealed among the trees.

Belanglo became synonymous with horror.

It was a place parents used as a warning: “Don’t pick up hitchhikers. Remember Belanglo.”

In 2010, the forest claimed another grim discovery.

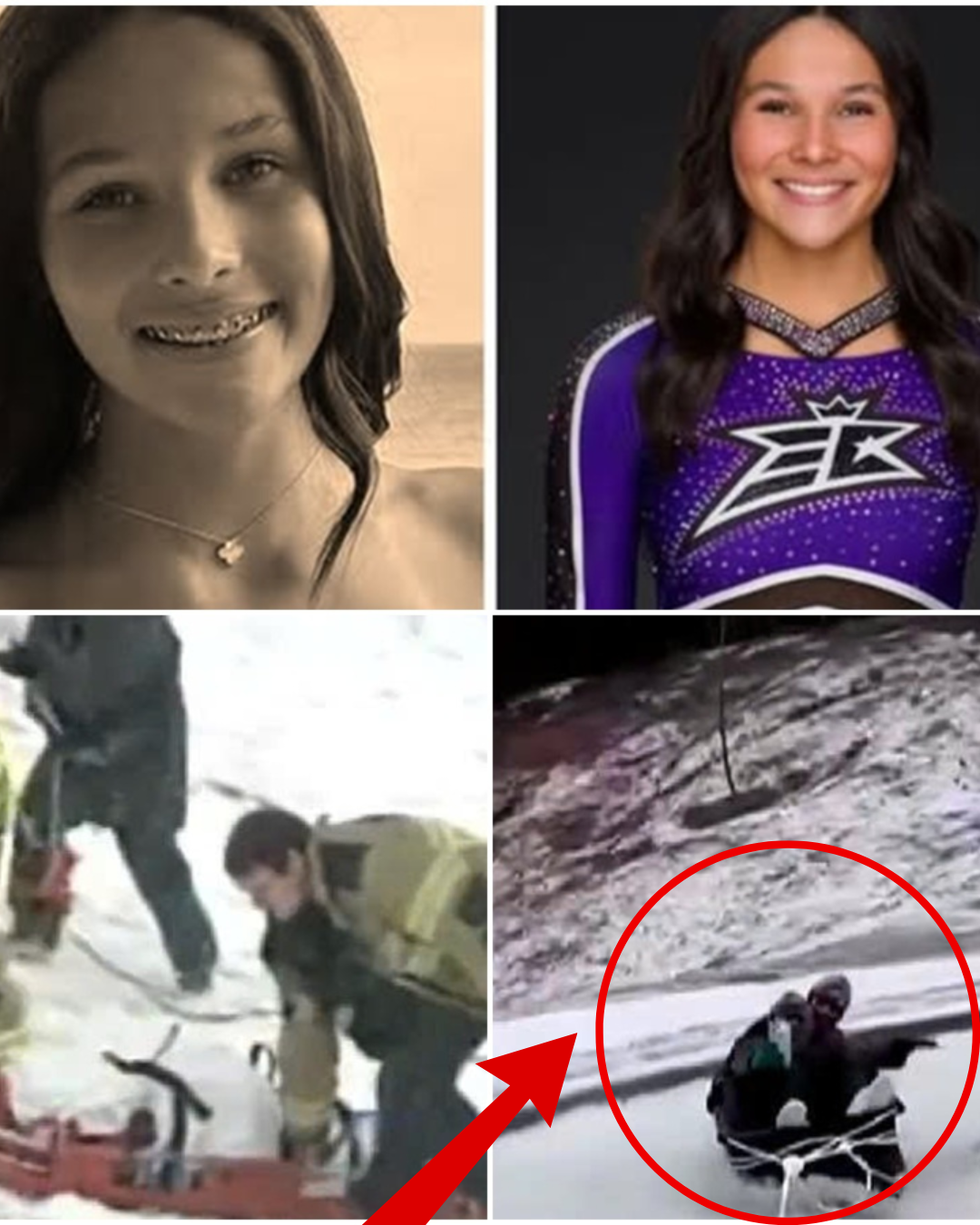

Trailbike riders came across skeletal remains, partially buried, hidden in the bush. Police were called, and forensic teams descended on the forest once more. They found the bones of a young woman. Nearby, within only a couple of metres, they also found a sock, an earring, and a size 10 Chain Reaction brand T‑shirt with the word “Angelic” printed across it.

That shirt had been sold in shops between 2003 and 2006. It was the kind of thing a young woman might wear casually — not designer, not expensive, just a piece of everyday clothing with a word that now felt cruelly ironic.

The woman’s identity was unknown.

She was given a reconstruction. Police released an image of what she might have looked like in life, hoping someone would recognize her.

They did not.

Her body stayed in the system as an unidentified female found in Belanglo — yet another victim in a place already haunted by that label.

No one knew, then, that her path and the path of the little girl in the suitcase were about to collide.

### Two mysteries, one breakthrough

In 2015, when the suitcase near Wynarka was opened and the child’s remains were recovered, it became one of the biggest mysteries in South Australia.

Who dumps a child beside a highway?

No missing‑person reports for a little girl seemed to match.

Photographs of the pink dress and the quilt were released. The quilt was homemade — the kind of thing a grandmother might stitch together with love, piece by piece, for a new baby. It was faded and degraded, but still recognizable.

News of the “suitcase girl” went national.

Crime Stoppers calls poured in.

One of them changed everything.

On October 8, 2015, a call came through — not the first, not the tenth, but the 1,276th call relating to the case. On the line was someone who believed they recognized the child.

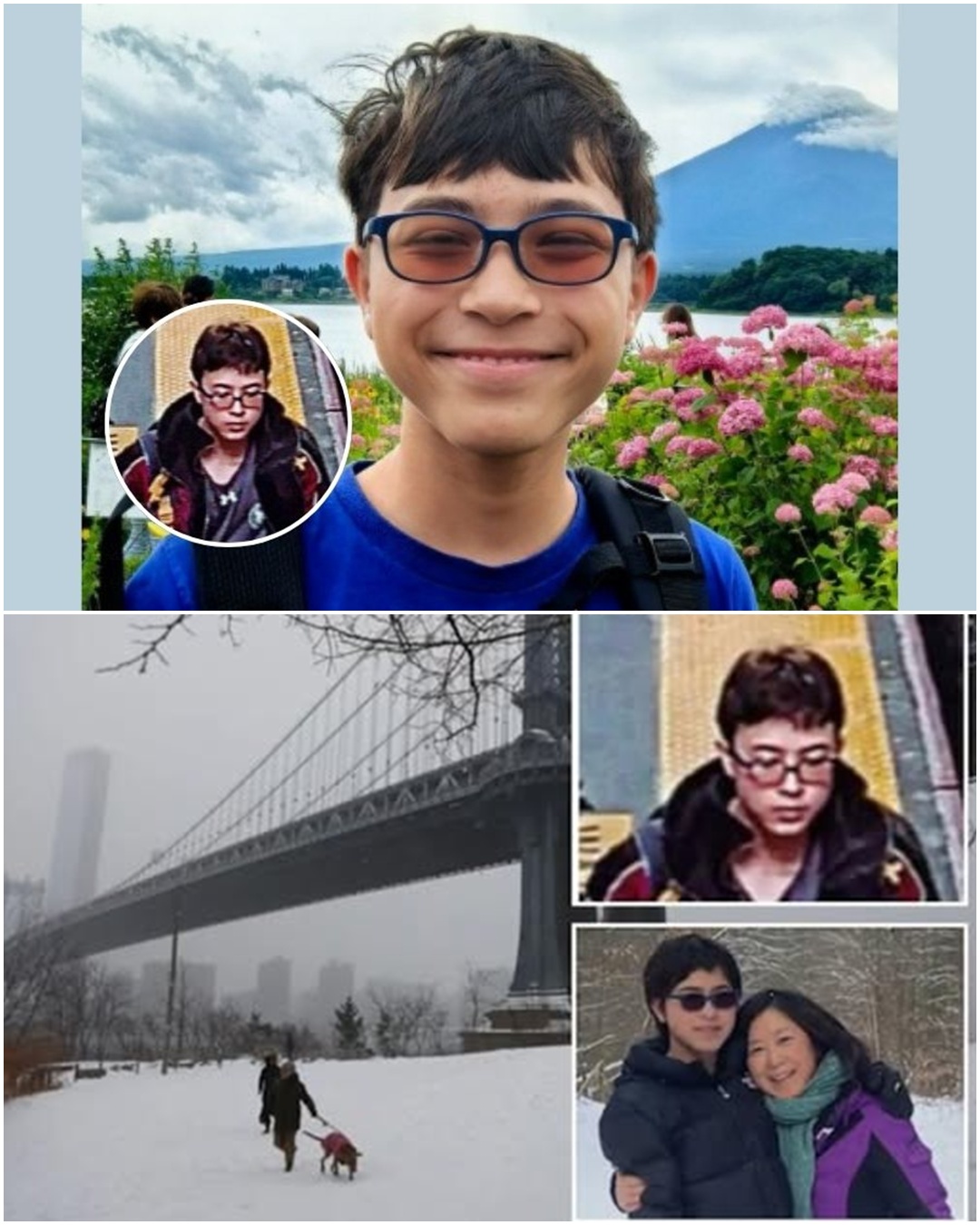

They thought the girl in the suitcase might be **Khandalyce Kiara Pearce**, a two‑year‑old from Alice Springs in the Northern Territory.

The caller hadn’t seen Khandalyce or her mother, **Karlie Jade Pearce‑Stevenson**, for some time. They believed they were missing.

It was the first real thread.

Police pulled it.

### A young mother on the road

Investigators dug into the new names.

Karlie Jade Pearce‑Stevenson was a young single mother from Alice Springs. She had given birth to her daughter, Khandalyce, in 2006. Between 2006 and 2008, she had left her family home with her little girl to travel and work around Australia.

Karlie was 20 years old.

She was last confirmed to have been seen driving a car with two‑year‑old Khandalyce on the Stuart Highway near Coober Pedy, in the Northern Territory, on November 8, 2008. The vast interior of Australia is stitched together by roads like the Stuart Highway — long, empty stretches where service stations are far apart and cars can travel for hours without passing another vehicle.

Young families, backpackers, truck drivers — all move along that ribbon of asphalt.

Some arrive at their destination.

Karlie and Khandalyce did not.

In September 2009, almost a year after they were last seen, Karlie’s mother reported her daughter and granddaughter missing. She told police she was worried. Karlie had been in sporadic contact, but had grown increasingly distant. Eventually, the contact stopped.

Then, something strange happened.

On October 9, 2009, just over a month later, Karlie’s mother withdrew the missing‑persons report. She had been reassured that Karlie was safe and well, but did not want family contact at that time.

For Karlie’s extended family, that explanation was painful, but plausible. People do sometimes break away. They move interstate. They cut ties. They choose new lives, especially when they’re young and chasing something different.

Those who loved Karlie believed she and Khandalyce were living somewhere else in Australia, safe, starting over.

They didn’t know that by then, both were already dead.

—

### The pink dress and the quilt

After the Crime Stoppers call naming Khandalyce, investigators began checking records.

They found a crucial witness — someone who remembered seeing a young mother with a little girl at **Marion Shopping Centre in Adelaide** in November 2008.

The witness had taken photographs.

In those photos, Khandalyce sits in a stroller, wearing a pink dress.

The same pink dress that had been found in the suitcase beside the highway near Wynarka.

The witness also had images of the stroller with a handmade quilt — the same pattern, the same fabric, as the degraded quilt recovered from the suitcase.

The hairs on the back of investigators’ necks must have stood up.

This wasn’t a vague resemblance.

It was identical clothing. An identical quilt.

Pieces that once belonged to a living child, now found wrapped around bones inside an abandoned suitcase.

Detectives from South Australia and New South Wales began working in tandem.

—

### The science that speaks for the dead

With a likely identity in hand, police turned to the records that don’t lie.

They checked government databases and immunization records for Khandalyce.

They found that she’d had her routine immunizations — and then nothing.

No more vaccinations.

No school enrollment.

No Medicare usage.

After a certain point, she simply vanished from the systems that track children’s lives.

That timeline aligned with the idea that she had died years earlier.

Next, they accessed her medical records, which included a stored blood sample. Using this, forensic experts compared the genetic profile with the skeletal remains from the suitcase.

The match came back positive.

The child in the suitcase was indeed **Khandalyce Kiara Pearce**.

Now, with her DNA, they could also test against the unidentified remains found in Belanglo.

When they compared Karlie’s DNA to the woman buried in the forest, the result was clear:

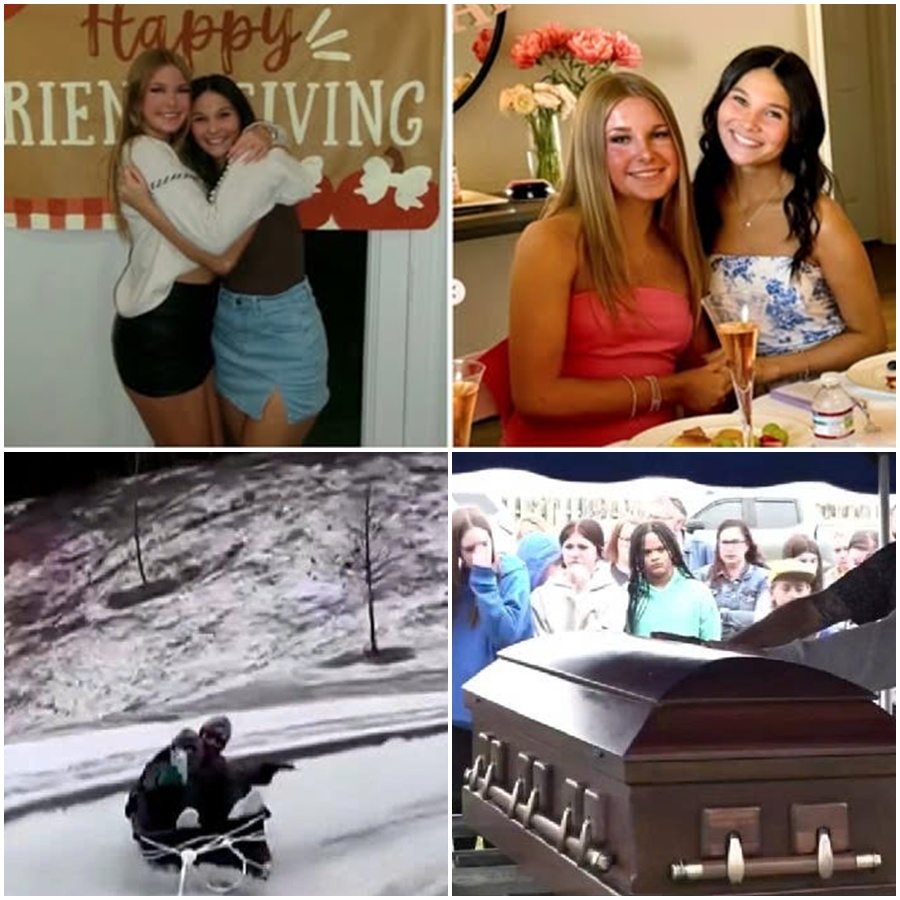

The skeletal remains in Belanglo State Forest were **Karlie Jade Pearce‑Stevenson**.

The young mother in the forest.

The little girl in the suitcase.

Mother and daughter, murdered and dumped in two different states, hundreds of kilometres apart, years earlier.

Two of Australia’s most disturbing cold cases had suddenly become one.

—

### “One of the most shocking crimes imaginable”

On a Wednesday in October 2015, detectives from New South Wales and South Australia stood before the media and revealed the breakthrough.

They named the victims: **Karlie Jade Pearce‑Stevenson**, 20, and her daughter, **Khandalyce**, two, from Alice Springs.

They explained the link between the Belanglo forest and the Wynarka suitcase — a link that added yet another shadow to a place already notorious as Ivan Milat’s killing ground.

South Australian Police Detective Superintendent Des Bray didn’t try to soften the truth.

“This is one of the most shocking crimes, shocking and unimaginable,” he said. “Another family has been torn apart and devastated.”

New South Wales Homicide Commander Detective Superintendent Mick Willing echoed the same horror. He confirmed that Karlie and Khandalyce had last been seen in late 2008 and were only reported missing in late 2009.

“Even after this time,” he said, “the extended family believed Karlie and Khandalyce were safe and well living interstate.”

They weren’t.

They were already lying, anonymous, in two different places — a forest and a suitcase.

—

### The long road they travelled

Detectives now had names and a basic outline. They knew when Karlie left Alice Springs. They knew when she was last seen on the Stuart Highway near Coober Pedy. They had evidence she’d been in Adelaide with her daughter in November 2008.

But the space between those points — the motels, caravan parks, campsites, highways, intersections, service stations, the faces they met along the way — was all a blur.

They needed to fill it in.

Det Supt Willing said homicide squads in both states were working closely “to complete the picture of Karlie’s life, particularly since the birth of Khandalyce in 2006.”

They appealed directly to the public.

“We are appealing for assistance from the community to help us identify their friends and associates as they travelled throughout Australia,” Willing said, “as well as landlords, motels, caravan parks or campsites where they stayed during this time.”

“Anyone who owns or operates these businesses is urged to check their records and help us piece this puzzle together.”

Det Supt Bray, head of Major Crime in South Australia, was blunt about the stakes.

“Those responsible for these horrific crimes remain amongst us in the community,” he said, “and they must quickly be caught and held to account for their actions.”

He described it again, plainly:

“One of the most shocking crimes imaginable; one that has not only devastated a family, but also had a terrible impact on the wider community.”

A young mother and child do not simply vanish and end up like this without people seeing something.

Police believed there were witnesses out there — staff who had checked them into rooms, travellers who had camped nearby, neighbours who had heard arguments, employers who had seen them working, friends or acquaintances who had shared drinks or meals with them on the road.

They needed those people to come forward.

—

### Belanglo’s reputation darkens

For Australians, the mention of Belanglo State Forest already carries a chill.

In the early 1990s, seven backpackers — three Germans, two Britons, and two Australians — were abducted and murdered by Ivan Milat. Their bodies were found in shallow graves, scattered in the forest. The case horrified the nation and made Belanglo synonymous with serial murder.

In 1996, Milat was convicted. He died in prison in 2019, unrepentant to the end.

Since then, the forest has drawn morbid curiosity and occasional copycat violence. In 2010, three teenagers, including one related to Milat, were arrested for the murder of 17‑year‑old David Auchterlonie. His body was found in Belanglo as well.

By the time Karlie’s remains were identified there, Belanglo already felt like a place where the worst things happen.

Her presence in that forest didn’t mean Milat killed her — he was already in prison when she disappeared — but it tied her death to the forest’s dark legacy.

Another young life.

Another set of bones.

Another story of violence buried in the trees.

—

### A family blindsided by horror

For Karlie’s family, the truth unfolded in reverse.

For years, they believed she and Khandalyce were alive somewhere in Australia. Karlie’s mother had died by the time the identifications were made. She never learned what had really happened to her daughter and granddaughter.

The rest of the family did.

They learned that the last time anyone could say for certain that Karlie and Khandalyce were alive was in late 2008, when they were seen travelling and visiting shopping centres.

They learned that Karlie’s remains had been resting in a forest since around 2010, unidentified.

They learned that Khandalyce had been dead for years before her little body was found in a suitcase by a South Australian highway.

They learned it all at once — not as a slow realization, but as a series of announcements and briefings that collided with the media coverage.

It’s hard to imagine that level of shock.

The guilt.

The what‑ifs.

The questions: Who reassured Karlie’s mother enough to make her withdraw the missing‑persons report? What exactly was said? What evidence convinced her that her daughter was simply choosing distance, not in danger?

We still don’t know all the answers.

But we know the result: a family that believed for years that their daughter and granddaughter were living quietly somewhere interstate had to face a reality far worse than anything they’d dared imagine.

—

### The man by the road

The image returns, again and again, in police appeals and media reports.

A well‑dressed man, around 60 years old, seen walking near Wynarka, carrying a suitcase along the Karoonda Highway weeks before the bones were found.

In a place where people don’t usually walk with luggage.

A place with more sheep than pedestrians.

He was seen. He was noticed. But he was not reported until after the suitcase was opened and the terrible contents were revealed.

We do not know who he is.

We do not know if he placed the suitcase there, or if he moved it, or if he has nothing to do with the crime at all.

But he is part of the story now — a question mark on two legs, a possible key to a timeline that still has gaps.

Police released descriptions, urged anyone who knew a man matching that description, in that area at that time, to come forward.

They made it clear: sometimes the smallest detail breaks a case open.

A motel check‑in.

A neighbour’s memory.

A stranger on a highway with a suitcase.

—

### A violent end

Detectives have never pretended that what happened to Karlie and Khandalyce was anything but brutal.

Khandalyce’s remains suggested a violent death. Police believe she suffered a vicious assault. The fact that her body was dismembered enough to be placed into a suitcase and left by a highway tells its own story.

Karlie’s skeleton showed signs of trauma too, recovered in a forest where so many others had been murdered. Her body lay exposed to the elements for years, losing soft tissue, losing details, until only bones and a few scattered belongings remained.

The timeline is stark.

Karlie and Khandalyce travel.

Karlie’s last confirmed sighting: November 8, 2008, on the Stuart Highway.

Witness sighting in Marion Shopping Centre, Adelaide, in November 2008.

After that: silence.

Family reassured, missing‑persons report withdrawn.

Years pass.

Karlie’s remains found in Belanglo in 2010.

Khandalyce’s remains found near Wynarka in 2015.

In between those dates, somewhere, the most crucial events occurred: the moments when their lives were taken. We still don’t know exactly where, when, or how, only that it involved cruelty, violence, and a deliberate effort to dispose of their bodies far apart, as if distance would erase connection.

It didn’t.

Science, persistence, and one crucial phone call did what the killer did not expect:

They put the family back together — mother and daughter named, linked, and remembered.

—

### A call that mattered

Crime Stoppers exists for a reason.

Most of the time, the public sees only the appeal posters, the phone number, the website. They don’t see the flood of calls, the false leads, the tips that go nowhere, the fragments that don’t fit.

In this case, South Australian Police made it clear:

It was call number **1276** that cracked the case.

Not call number one.

Not call number ten.

Number 1276.

One person, who had been thinking.

One person, who had noticed that they hadn’t seen a young mother and child for a long time and that something about the “suitcase girl” felt wrong.

One person, willing to pick up the phone and say: “I think I know who she is.”

That call led to names.

Those names led to records.

Those records led to DNA comparisons.

Those comparisons led to the truth.

Without that call, the little girl in the suitcase might still be “unknown female child, aged 2–4.”

Without that call, the woman in the forest might still be “unidentified female in Belanglo.”

It’s a reminder that in cases like this, the smallest act — a phone call, an email, a remembrance — can shift the entire story.

—

### A puzzle that still needs pieces

When police stood before the cameras and revealed the identities of Karlie and Khandalyce, they did not say,

“It’s solved.”

They said,

“We know who they are. We still need to know what happened to them.”

Det Supt Bray put it simply:

“Those responsible for these horrific crimes remain amongst us in the community.”

They are out there.

Maybe older now.

Maybe living quietly.

Maybe laughing with friends, going to work, shopping in supermarkets, driving the same highways where they once dumped a suitcase.

Police urged anyone who had seen the young mother and her little girl travelling in the years before their deaths to come forward. Anyone who runs a caravan park, motel, or campsite, who might have checked in a young woman from Alice Springs with a toddler around 2006–2008, was asked to search their memory, their old guest books, their archived records.

They appealed nationally, across states, because Karlie and Khandalyce had travelled widely. They could have crossed paths with people anywhere: in the Northern Territory, South Australia, New South Wales, or beyond.

Every memory matters.

Every half‑remembered conversation.

Every stray photograph in someone’s old phone or digital camera.

—

### Why this story stays with us

There are many murders.

There are many disappearances.

But some stories carve themselves into the public conscience in a particular way.

This one does, because of the details.

A two‑year‑old girl in a suitcase beside a highway.

Her mother’s bones in a forest infamous for a serial killer.

A grandmother who made a quilt for a child she loved, never knowing that the quilt would one day help identify her granddaughter’s remains.

A young mother, barely out of her teens, trying to build a life on the road, her car seen for the last time on a long, unforgiving highway.

A family reassured, for years, by lies they thought were truths.

Detectives describing the crimes as “shocking and unimaginable” — and meaning every word.

We don’t have to know every gory forensic detail to feel the weight of it.

We only need to understand this:

Karlie and Khandalyce were real.

They were loved.

They were travelling, like so many young Australians do, trying to find work, trying to see more of their country.

They crossed paths with someone who chose to use that freedom against them.

And even after their deaths, the person who killed them tried to erase them — separating their bodies, leaving them where no one would connect them.

It almost worked.

Almost.

—

### Remembering their names

Now, when we talk about this case, we don’t say only “suitcase girl” or “Belanglo remains.”

We say:

**Karlie Jade Pearce‑Stevenson.**

**Khandalyce Kiara Pearce.**

Mother and daughter.

From Alice Springs.

Killed, separated, dumped in two different states.

Identified because someone cared enough to make a call, and because detectives in two jurisdictions refused to give up on their unnamed dead.

Police are still asking for help.

They’re still urging anyone with information — no matter how small — to contact Crime Stoppers on **1800 333 000** or via the online reporting page.

Because while the breakthrough answered one set of questions — *who* they were — the bigger questions still remain.

Who did this?

Why?

Where, exactly, were their last days spent?

Who else saw something and hasn’t spoken yet?

Until those questions are answered, there is still work to do.

For now, we sit with what we do know:

A suitcase on a highway.

A forest with a terrible history.

A young mother and a little girl who didn’t deserve any of it.

And a country that, at last, knows their names.